I begin today with a tangential rant.

Around the end of September, I was hanging out with a friend of mine who I knew from my college radio days. He remarked that the evening that we were together was the 31st anniversary of Nirvana's Pittsburgh show at Graffiti. (This, of course, is the one that Nirvana fans and native Pittsburghers all remember as the night when the band set the couch in the dressing room on fire, quite possibly in retaliation to the booking agent who wanted a cut of their merchandise sales. You can't mention that show in Pittsburgh without that adjacent story.)

That show has gone down in history because, of course, it happened right as Nirvana was hitting it big - really big. Big enough for punk rock to "break" as a film about several bands from that period would later opine. I know many people who were there but I was not one of them. I had just played a show with my long time favorite band Trotsky Icepick and in a few weeks would see Sebadoh, who unexpectedly blew my mind in a way that hasn't been the same since. (I was also dealing with relationship issues, but that's irrelevant right now.)

Besides, at that time no one would have predicted that a band who was part of the grunge scene - which was still pretty much a catch-all term for Pacific Northwest bands - would take their major label debut and knock it out of the stratosphere, unlike anyone else up to that point. In September 1991, Nirvana was just another band on their way up. People who liked them were ready to check them out but no one had any idea that they were witnessing legends in the making. .

And that's the reason why it's important to go out to shows and check out live music. You never know where an artist is going to be in a few months. You never know how moved you might be by someone's set. Sure, the specter of COVID-19 still lurks in every corner, but people and venues are playing it safe. If you bring your mask, you should be in a good shape. There's no guarantee you walk out of a show feeling like you're reached nirvana (pun intended), but you have a greater chance of witnessing some legend in the making just be being out and about. And as many people have said, you've got to dig it to dig it.

Which brings us to the 52nd Annual Pitt Jazz Seminar and Concert, which started this week and continues for the next few days. In years past, the seminar welcomed jazz musicians to the University of Pittsburgh, where they gave free lectures on topics ranging from their careers to the industry to the music itself. It would culminate in a Saturday evening concert that was reminiscent of the Jazz at the Philharmonic shows: a blowing session that put together musicians that may or may not have ever been on the same stage at the same time.

The whole thing was spearheaded by the late Dr. Nathan Davis in 1970, who brought in a pretty high caliber group of friends, some of which who showed up fairly regularly over the years. When Geri Allen took over the position in 2013, the template remained, though the shows started to think outside the box a bit more. Then in 2019, Nicole Mitchell became director of Jazz Studies and presented a concert that included more grounded players like Rufus Reid (bass) and Jason Moran (piano) together with outliers Roscoe Mitchell (saxophones) and Moor Mother (spoken word). Some friends described the evening as a train wreck and audience members expecting to hear a group blow on something like "Killer Joe" left en masse before things were done. (

My take on the night can be found here.)

Post-pandemic, things are a little different for Year 52 of the event, which has the title "We Are All Jazz Messengers." First of all, IT'S ALL TOTALLY FREE! Not in style, but in dollar amount. None of the performances cost anything! Anyone curious to see a pianist who's played with Archie Shepp and Pharoah Sanders and David Murray? Well, you could have seen him this week, without even touching your wallet.

Dave Burrell, the pianist in question, played at the Bellefield Hall at the University of Pittsburgh on Tuesday, November 1. His appearance coincides with the donation of his archives to the Center for American Music, part of the University of Pittsburgh Library System, which also houses Errol Garner's archives. To kick off the Tuesday night show, Ed Galloway, Associate University Librarian for Archives and Special Collections, presented Burrell with a plaque commemorating his career and donation to the university (below).

The evening featured Burrell in a trio with bassist Joshua Abrams and drummer Hamid Drake, with flutist Nicole Mitchell joining them. (Mitchell just announced her departure from Pitt for the University of Virginia about a month ago. Aaron J. Johnson is now the Acting Director of Jazz Studies at Pitt). But before the whole group played, Burrell sat down at the piano for a long, flowing medley. While he has played with the fiery intensity of someone like Cecil Taylor - reaching his left hand over his right to literally stab the upper register of the keyboard during a solo - the pianist can also reveal a delicate, if no less deep, side by exploring some standards. For about 15 minutes, my ears heard traces of "Autumn Leaves," "Here's that Rainy Day," "How Deep Is the Ocean" and "My Melancholy Baby." The latter two featured some solid stride work in the left hand, pushing the music forward.

The evening had a pretty casual feel to it, as if the band might have been coming up with ideas on the fly. The whole group came out onstage but Burrell announced that he and drummer Drake would begin with a duet, which sent Mitchell and Abrams backstage again. The two players dug into a tune with a boogie groove to it, with Drake emphasizing the offbeats at one point and playing double-time the next. After a few minutes, Burrell decided it was time for Drake to go it alone, and the pianist himself left the stage.

This move was something that Thelonious Monk used to pull on drummers that got on his bad side, but Drake hadn't done anything to offend the evening's honoree, as far as we could tell. Besides, Drake had more than enough ideas to keep the audience eyes glued to the stage, with a brilliant range of press rolls. hi-hat whacks and more use of offbeats.

Mitchell and Abrams had their duo time next with the flutist vocalizing as she blew and Abrams producing a series of thick double stops, alternating between bowing and plucking. Despite the casual feeling of the show, the rapport between the players was on display. Drake, Mitchell and Abrams all know each other from their time in Chicago in and around the AACM so that kept things flowing.With Burrell back with them, a free, open section eventually morphed into "Come Rain Or Come Shine" which the group took their time digging into, exploring it to a great degree. That song especially is one that's been performed thousands of times, but the quartet approached it with that understanding. They weren't there to simply get a rise from the audience by playing something familiar, nor did they turn it inside-out. They presented in a way that proved

why it's such a lasting classic.

Last night (Thursday, 11/3), Burrell appeared in a panel discussing his career, along with his wife, the poet/author Monika Larsson and Pitt Associate Professor of Jazz Studies and author Michael Heller (the latter whom kept pronouncing the pianist's surname "BYOR-ell" rather than "BOOR-ell" as everyone else seems to have said it; maybe he's on to something we don't know?). Via Zoom, the discussion also included trumpeter Ted Daniel (seen below), saxophonist David Murray and jazz author John Szwed.

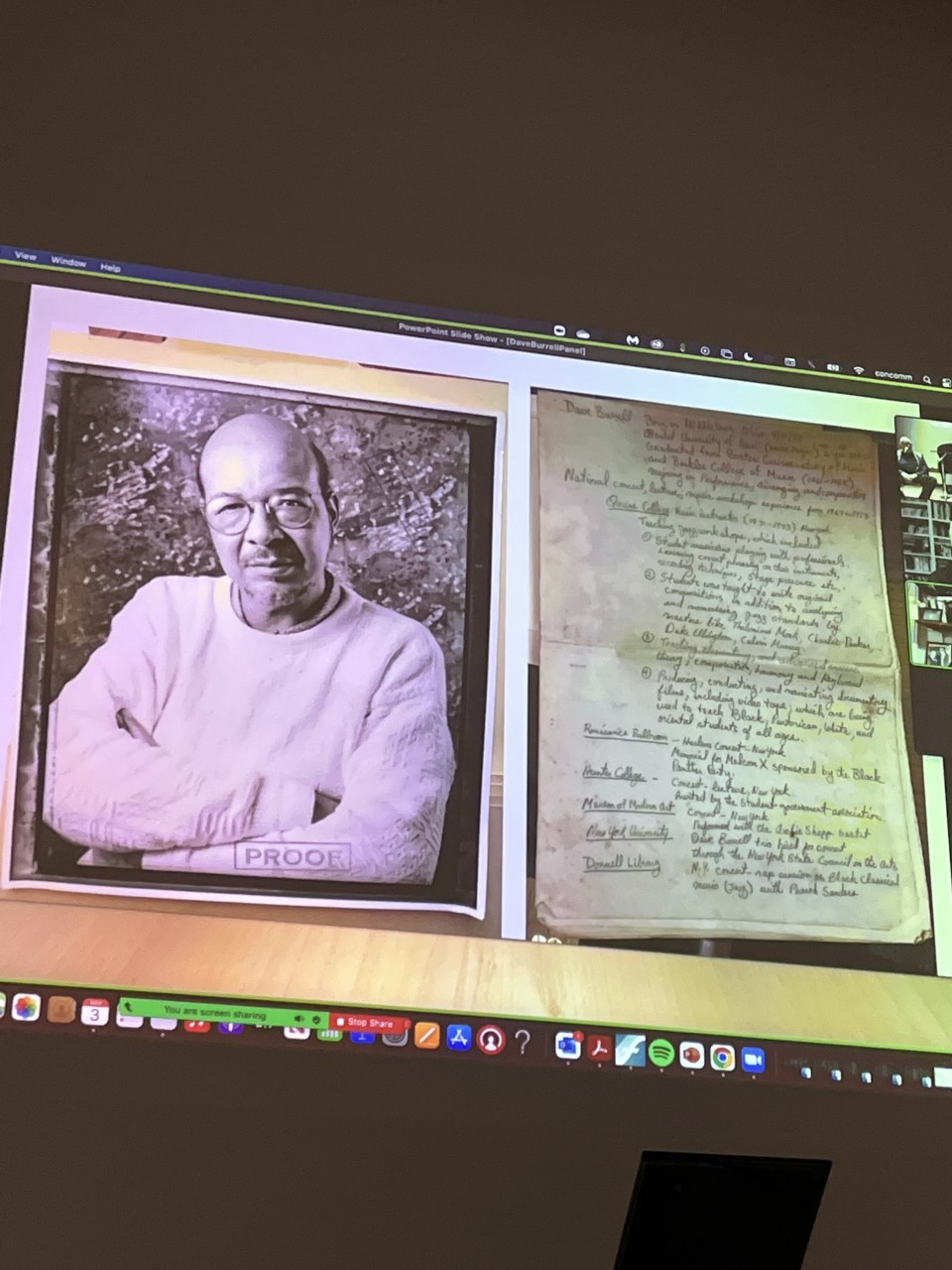

Heller presented a few shots of items from the Burrell archive, as seen above here in the one shot I got of the overhead projection. The image on the right is actually an early resume that Burrell put together.

Though the Zoom connection sometimes make things a little hard to hear or contextualize, it provided some fun insight into Burrell's wide-reaching connection with the different players. Daniel (seen above) recalled meeting him at the Berklee School of Music in the early '60s, where Burrell showed "determination and consistency with practicing," and introduced the young trumpet player to the Thesaurus of Scales and Melodic Patterns by Nicholas Slonimsky, a book which he said he still owns to this day. The two players also reminisced about a trip to Europe that took them to a festival "in a cow pasture in Belgium" where they shared a bill with not only the Art Ensemble of Chicago but also Pink Floyd, the Mothers of Invention and Cream.

Larsson talked about writing a libretto for Burrell's music and how a midnight cup of coffee lured her away from her then-husband to the pianist. Murray discusses the duo shows he and the pianist performed, along with the latter's tenure in Murray's octet. Burrell chuckled as he remembered what he would say to drummer Ralph Peterson before a performance: "Time to make the donuts!"

After the panel discussion, members of the Pitt Chamber Ensemble performed some of Burrell's work for strings and piano, followed by trumpet and piano. After Tuesday night's performance, these modern pieces with flowing melodies offered another take of what the pianist has created.

If you read this in time, the Pitt Jazz Faculty will present the final on-campus concert on Saturday, November 5. The show will consist of music by Art Blakey. 7:30 pm at Bellefield Hall. It's free! Be there to dig it!